The Curious Case of “Filtering”….or How to Change Your Mind

As we head into 2025, we will see major changes in the macro-political environment. Keep in mind your assumptions may not always be true.

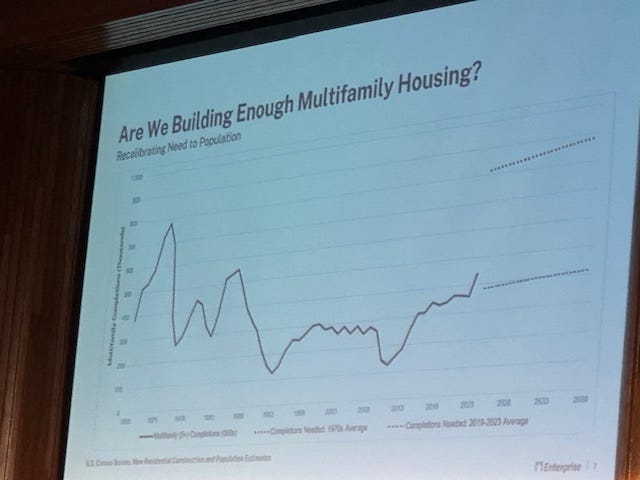

Shortly before Christmas, I attended the national conference of the National Association of Affordable Housing Lenders (thanks to my friends and colleagues Doug Schaeffer and Noelle Lentz for the invitation!) and one of the main keynotes focused on the 8 million person housing crisis. The punchline: *today* we are building about 500,000 multifamily units less each year than demand, and that will jump to 1 million shortage, per year, in the next 15 years.

You could see this and assume an answer would be, “build more housing,” no? But that’s not what the keynote speaker said. He said, “As we look at what we can do to promote more housing…we need to be deeply engaged in what kind of housing, and how affordable. There is an argument for what’s called “filtering,” which means that market-rate housing introduced increases supply, and that generally brings rents down across the board…but we just don’t know if filtering is true.”

This is the most common argument I hear against building more (unsubsidized, market rate) housing…that it won’t actually matter to “the people who actually need housing” (a pretty vague stalking horse.) And it is an argument that I generally bought at an early stage in my career—and can be a seductive one. Why does anyone need more high-end apartments with luxury amenities?

Except for—the evidence is strong: filtering DOES work!

Economist Jay Parsons recently said: “ I was once a skeptic of rental housing “filtering” — the theory that new “luxury” apartments pull higher-income renters out of moderate-priced rentals, thereby benefiting moderate-income renters, and on down the line. I am no longer a skeptic. I became a believer last year after realizing I had made several mistakes in my analysis — mistakes I still see others making today.”

Reviewing the research, there’s four key misconceptions:

High-supply areas are where you see the most filtering: Filtering is most visible in neighborhoods with significant new construction. Realistically, there are where the largest housing shortages are. As an example, Austin, TX has been a top-5 population growth city over the past ten years. It has seen more supply per capita than any other city. And rents have declined 3-7% over the past 12 months as much of the new supply has hit the market. 30,000 new units in Austin can bring down all rents in aggregate. If you have a city like a Rust Belt Midwestern medium-size cities, with low supply, and you introduce one or two large luxury units that raise rent relative to what is on the market, filtering may be less likely to happen. Treating high-supply and low-supply areas the same can obscure the impact.

Apartment construction in Austin, Texas

Rent levels are more important than classifications: There are categories that are framed by economists and brokers (e.g. Class A, Class B, Class C) that can obscure analysis. If a bunch of Class A units are added, and bring up average Class A rents—we often see Class B and Class C being more affordable, as the highest income renters are now going for the new Class A units, versus over-bidding lower-income renters for Class B and C units. Filtering needs to be analyzed through rent levels, which directly reflect affordability shifts.

Supply Must Be Relative to Demand: As Parsons noted, supply has to outpace demand to make a real impact. Simply building more isn’t enough—it needs to be significant enough relative to demand. In the 2010s, construction fell short, even in booming states like Texas, which made it harder to see the effects of filtering. But in 2023-24, with a noticeable increase in new housing supply, we’re finally seeing rents drop, including for lower-cost properties.

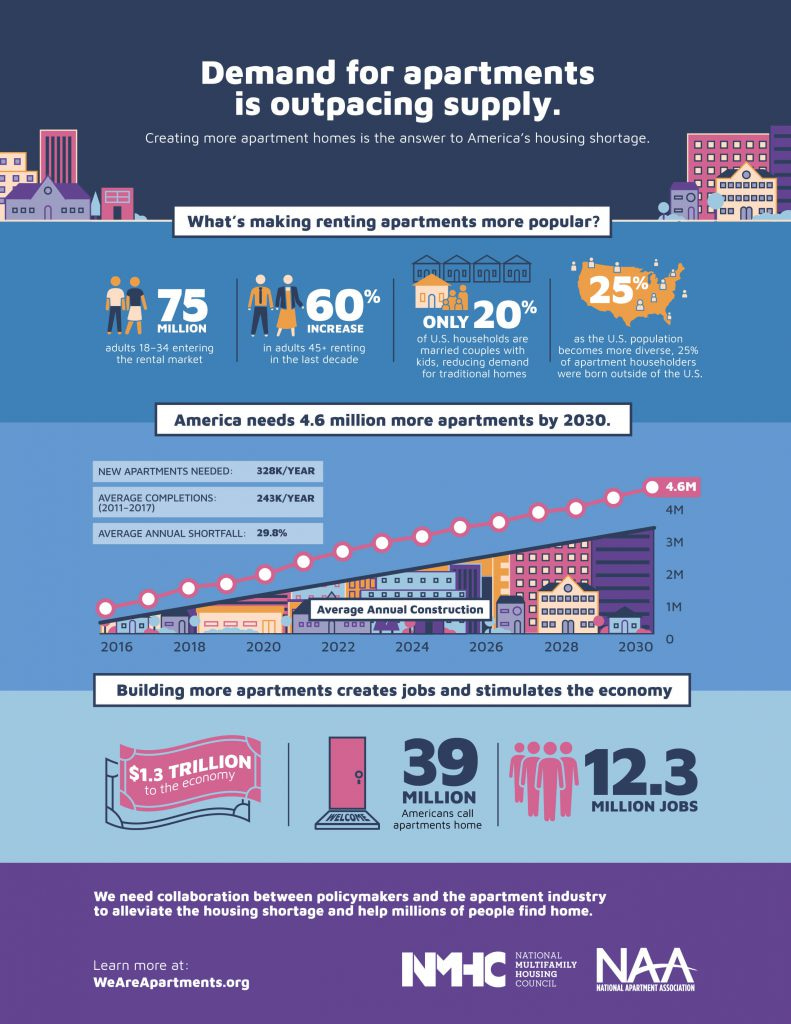

The National Multifamily Housing Council tries to explain WHY apartment demand continues to skyrocket.

Lots of New Research: What I most frequently hear from skeptics is “filtering may make sense in theory but I haven’t seen the evidence.” This was probably true five years ago. However, filtering has been a subject of much more intensive academic study as housing construction increases, and shortages become more acute. Three good recent pieces include Evan Mast (2023), Kevin Erdmann (2022), and the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis (2024).

Finally, in the words of Jay Parsons, “staying open to admitting errors — as I did — is crucial for understanding this issue fully!”