I’ve been surprised (pleasantly) to see housing become a major election issue, and I started writing about it. I wrote so much that it became a two-part post.

There are *many* reasons to vote for or against a candidate, and I am not a single issue housing voter. However, I do find it instructive to figure out what each candidates (and political parties if they control the House or Senate) might do- to try and get the best outcome.

Please note, dear readers, that this is a draft (and just my thoughts alone). I think—and hope!—that housing remains a major political issue and if you have thoughts/additions/disagreements please add as I am sending this out as a “first draft” to all of you to sharpen my own thinking, too.

The Housing Crisis

The U.S. is in a housing crisis. Depending on the source, there’s a shortage of between four and 7.3 million homes. Over 40% of renters are "cost-burdened," spending more than 30% of their income on housing. Public opinion reflects the severity, with nearly half of U.S. adults identifying affordable housing as a major issue, a 20% increase in just five years, particularly affecting low-income households.

In politics, housing has moved from nowhere to the front page. In the race to solve America’s housing crisis, Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump have each talked about (with different levels of detail). Both I think instinctively recognize the severity of “the rent is too damn high”, but their solutions certainly show the deeper ideological divides on how each party might address this crisis.

Harris, in line with progressive Democrats, emphasizes regulating corporate landlords and capping rent increases. Trump leans on supply-side economics, promoting deregulation and tax incentives to “build, baby, build.”

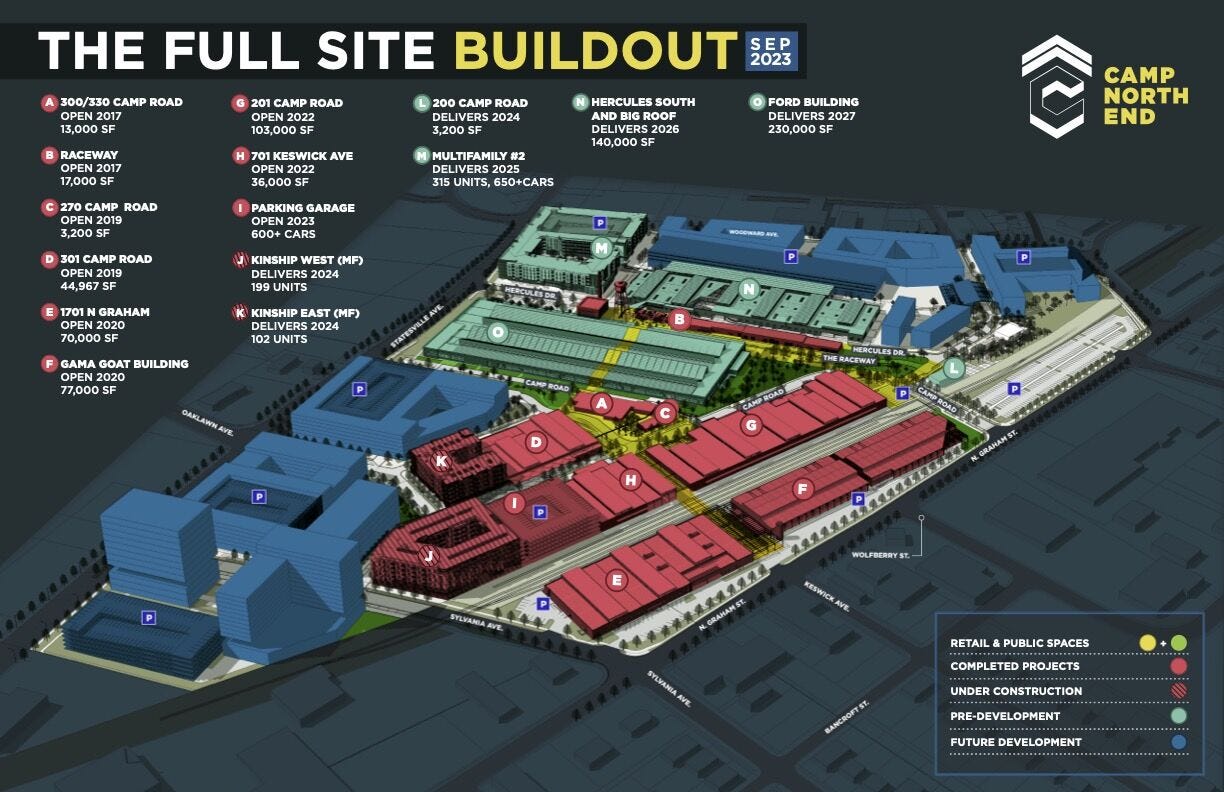

Camp North End, which I discussed in a prior post, aims to add 700 market rate units to Charlotte’s 30,000 housing unit shortage. There may be stronger affordability metrics through state and local public-private partnerships.

But what’s truly at stake in these policies? Are we risking long-term affordability by focusing on rent caps? Does encouraging builders just subsidize luxury apartments, or do we need to apply? Or are there better solutions hiding in plain sight?

Why housing is like energy 25 years ago

The housing shortage today is like the energy shortage at the beginning of the ‘Aughts. Twenty-five years ago, the U.S. faced significant energy shortages, heavily dependent on foreign oil, with concerns about dwindling domestic production and rising fuel prices. 9/11 and oil concerns led to a decade or morre of military adventures in the Middle East. Domestic oil production had been in decline since the 1970s, and there was little emphasis on renewable energy sources.

The story has completely changed. Todaay, U.S. enjoys an energy surplus due to a dramatic increase in shale oil and natural gas production, made possible both by fracking and renewables.In 2003, renewables contributed just a small fraction to the energy grid, while in 2023, renewables provided 21.5% of U.S. electricity, and projections suggest this will continue to rise. Combined with increased oil and gas output, the U.S. has shifted from being energy dependent to an exporter, balancing both traditional fuel production and clean energy initiatives.

As energy production has changed, so has politics. Kamala Harris, for example, initially supported banning fracking, aligning with more progressive environmental stances. However, in 2024, her position has evolved to an "all-of-the-above" energy policy. This change could be seen as a strategic move to appeal to voters in energy-dependent states like Pennsylvania, where natural gas production is crucial to the economy. By embracing a broader approach, she signaled flexibility while maintaining a commitment to clean energy investments.

There’s an ideological division in the U.S., but I believe we ought to pursue an “all of the above” in housing.

Harris’s Housing Plan: Regulating Rents, Supporting Renters and Homebuyers

In her campaign stops, Vice President Harris has repeatedly pushed for measures like rent caps and stronger protections for renters. During a recent speech in Atlanta, Harris pledged to “take on corporate landlords” by capping unfair rent increases and targeting companies that engage in price gouging. She has endorsed President Biden’s proposal to limit rent increases to 5% for landlords with over 50 units, aimed at curbing what she calls “exploitative” practices in the housing market.

Harris’s plan is also deeply rooted in addressing income inequality and preventing displacement. Her proposal includes $70 billion to address the capital needs of public housing units and $25,000 in down payment support for first-time homeowners. The idea is to make it easier for lower-income families to access homeownership while protecting renters from rent spikes that they can’t afford.

Trump’s Housing Plan: Build, Baby, Build

In contrast, Donald Trump’s approach to housing centers on the idea that increasing supply and reducing regulation will naturally drive down costs. His plan and platform is less detailed for 2024, so we can probably best guess at what he might do by looking at the last administration.

I worked most closely with the last GOP Administration on the Opportunity Zones program, which incentivize development in underserved areas through tax breaks for investors, which I believe has had a significant impact: one in five housing units today under construction are in Opportunity Zones.

The Trump Administration also proposed opening up federal land for new housing development, believing that by easing restrictions and cutting red tape, developers could more easily build the kinds of market-rate housing that are in short supply. The use of government assets for housing has attracted interest from both parties, though Republicans have more frequently been critical of local zoning laws, particularly single-family zoning, which can limit housing density and thus contributes to high prices. Finally, the administration’s plan to end conservatorship of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac also aimed at freeing up more capital for homebuyers.

At first glance, Harris’s focus on renters and Trump’s focus on builders seem to tackle two sides of the same coin. Critics of the “supply-oriented” plan warn about the potential to merely subsidize luxury apartments, and critics of the “demand-oriented” plan point out that rent controls will merely just constraining supply.

But the more you dig, the clearer it becomes that these plans might have radically different outcomes on affordability.

A Pro-Builder Economy: The Case for More Market-Rate Housing

My friend Bruce Katz’s recent piece for the National Housing Crisis Task Force offers an important insight: the only proven way to make housing more affordable is to build more of it. Katz emphasizes that supply-side constraints—like restrictive zoning laws, high land costs, and complex permitting processes—are a key factor in driving up prices. In cities like San Francisco and New York, where regulations make it nearly impossible to build new housing at scale, rents have skyrocketed, leaving low- and middle-income renters scrambling for options.

Market-rate housing, even if priced out of reach for some, does depress all rents. As newer, more expensive units come online, older units tend to become more affordable, freeing up stock for renters with lower incomes. A real-world example of this can be found in Minneapolis, which in 2019 eliminated single-family zoning across the city. The move sparked a surge in new apartment developments, which has, over time, started to stabilize rent prices. Even though much of the new construction is market-rate, it’s reducing the upward pressure on rent prices for older units.

The Current Supply Boom Easing Rents-and the Coming Supply Cliff

The U.S. is currently experiencing a multifamily housing supply boom, with approximately 565,000 new apartments delivered nationwide in 2023, the most since the 1980s.. Let’s take the country’s two fastest-growing cities over the past five years: Austin and Phoenix. For instance, Austin saw rents drop by 4.7% in 2023 due to a surge in new units, Phoenix also recorded a 3.2% rent decline as supply outpaced demand. However, new multifamily supply is expected to slow, with multifamily permitting dropping by 20% in 2023, marking the lowest level since 2020.

Austin is expected to drop in supply 75%

Building is plunging nearly everywhere

I’m firmly in the camp of supporting the “pro-builder” policies in addressing the gap. When more units (of all income groups) are built, rents fall. And we are about to see a *massive* drop-off in new units, which will likely mean substantially rising rents in in-demand cities like Austin and Phoenix.

The “Pencil Problem”: Why We Need Pro-Builder Policies

In a recent meeting with Jared Bernstein, the head of the Council of Economic Advisors for the White House, he cited the top supply problem as “the Pencil Problem”—the fact that building reasonably affordable units no longer "pencils out" for developers in 2024 due to skyrocketing costs and interest rates. Construction costs have surged by 30% since 2020, driven by labor shortages and higher material prices like lumber. Additionally, the Federal Reserve’s aggressive rate hikes have more than doubled financing costs.

Any housing policy needs to solve “the pencil problem.”

Can cash solve the pencil problem? Why not subsidize affordable unit construction?

The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program is the largest federal subsidy for affordable housing, financing around 50,000-60,000 new units annually. It works by offering tax credits to developers who agree to cap rents on a portion of their units. About 10% of units under construction are LIHTC, with a cost to taxpayers estimated at about $13 billion a year. (By comparison, about 20% of units under construction are in Opportunity Zones, with a de minimis cost to the taxpayer).

LIHTC can be a great tool to solve part of the “pencil problem”, but it is only a small part of the solution. Most developers hesitate to pursue LIHTC deals due to complex application processes, income restrictions, and long-term compliance burdens. Additionally, rising construction costs and delays in receiving tax credits can make these projects financially unappealing, especially when compared to market-rate developments.

I have a friend who is a highly passionate, purpose-driven LIHTC developer-one of the best!-and truly is committed to solving the affordability crisis. And he frequently discusses how difficult it is. He once described the extreme brain damage of developing low-income, government-subsidized housing as such:

“Who would want to do this?! I have a theory. As a kid, we would sometimes throw rocks at each other because throwing rocks at your friends is simple and fun. A few of those kids (me) not only enjoyed throwing the rocks, but we enjoyed being hit with them. Or almost being hit with them. The anticipation of pain, and the sporadic encounter with it, is thrilling to a select few. Now, as you get older, you can’t convince people to throw rocks at you because of crime. So people are forced to pick new outlets to scratch that itch.

I will sporadically go to a State Housing Agency and ask for a bunch of subsidies to develop low-income housing. Their particular mood that day typically dictates the size of the rock they will use and the velocity with which they will send it in my direction. I ask for some money, and as the angry lady behind the desk looks for a rock to throw at me, a twinge of excitement runs through me because I’m back in the game. Let’s build some f’ing housing.”

Most builders do not enjoy trying to do the right thing while having rocks thrown at them. And we need all the builders we can get these days.

The Challenges with a Pro-Renter-Only Economic Plan

Many politicians are rightly focused on renters because they represent a significant and growing portion of the U.S. population. As homeownership has become increasingly out of reach for many, the rental market has expanded, especially in urban areas where housing costs have surged. Renters are often more vulnerable to economic instability, facing issues like rapid rent increases, displacement, and inadequate protections. With over 40% of renters classified as "cost-burdened," political leaders recognize that addressing these challenges is crucial to ensuring housing security for millions of Americans.

If rents are rising, the Harris campaign would ask, why don’t we just cap them?

The Evidence on Rent Control: Does It Really Impact Rents in Targeted Areas?

Rent control policies have long been a controversial tool in efforts to combat rising housing costs. Advocates argue that rent controls protect vulnerable tenants from being priced out of their homes, while critics warn that they distort housing markets and exacerbate long-term affordability issues. The evidence, based on numerous studies and historical examples, suggests a nuanced picture: while rent control can offer short-term relief to tenants, its long-term effects often include reduced housing supply, disinvestment in rental properties, and increased prices in non-regulated units.

Rent Controls Do Create Short-Term Relief for Tenants

Rent control policies generally work by capping how much landlords can raise rents each year, particularly in areas where housing costs are rapidly increasing. In the short term, this provides stability for tenants, particularly low-income renters, allowing them to remain in their homes without the threat of unaffordable rent hikes. This stability is the primary argument in favor of rent control.

For example, in New York, where rent control has been in place for decades, tenants in rent-controlled units pay significantly less in rent than those in market-rate units. According to a study by the Furman Center, rent-regulated apartments are often priced well below market value, with tenants of regulated units in Manhattan paying about 45% less than those in unregulated units in similar neighborhoods. This price stabilization benefits those who secure rent-controlled units and can help alleviate displacement and gentrification pressures in some communities.

Similarly, San Francisco, another city with rent control, saw substantial rent savings for tenants who were lucky enough to occupy controlled units. A study by economists at Stanford found that tenants in rent-controlled units between 1994 and 2010 saved up to 25% compared to those in unregulated units.

Negative Impact: Reduced Supply and Higher Prices in Unregulated Units

However, while rent control provides immediate relief to tenants, its long-term effects can be counterproductive. Rent controls do reduce housing supply. When landlords face limits on the returns they can earn from their properties, they may decide not to invest in building new rental units or maintaining existing ones.

The same Stanford study on rent control in San Francisco found that the policy led to a 15% reduction in the supply of rental housing. Landlords either converted rental units into condominiums, sold them, or simply stopped maintaining them. As a result, while rent control kept prices low for tenants in regulated units, it actually contributed to higher rents in unregulated units by shrinking the overall supply. The study concluded that rent control in San Francisco increased citywide rents by about 5.1%.

Economists generally agree that rent control discourages new construction and investment in rental housing. A survey conducted by the IGM Forum at the University of Chicago found that 81% of economists agreed that rent control reduces the quantity and quality of housing. By creating an artificial price ceiling, rent control distorts the incentives for landlords and developers to build or maintain properties, leading to fewer housing options for future renters.

Quality of Housing and Landlord Behavior

Another unintended consequence of rent control is its impact on the quality of housing. When landlords cannot raise rents to cover rising maintenance costs, they may defer repairs or lower the quality of services provided to tenants. This results in deteriorating housing stock over time, particularly in areas where rent control is strict.

In New York City, a 2019 study found that rent-controlled units were more likely to experience maintenance issues compared to market-rate units(Harris Housing Plan). This is a common problem in rent-controlled areas, where landlords, faced with a limit on potential rental income, may invest less in upkeep or even seek to remove units from the rental market altogether.

What happens when you remove rent controls?

A recent WSJ article highlighted how Argentina, another housing-starved country, removed rent controls, which led to a dramatic improvement in its housing market. We saw several outcomes:

· Housing supply surged by over 170%, encouraging builders to invest in new rental units.

· Rent growth slowed to a three-year low, disproving fears of skyrocketing prices. With more rentals available, renters found it easier to secure homes, often at better prices than before.

· The increased housing supply also helped to cool inflation, as housing costs were previously a major driver of overall inflation.

Next post: ideas that bridge the gap where I see promise

Of course “the rent is too damn high,” and of course the construction of highest-possible-rent multifamily alone will not solve the problem. But the tools at the federal level today are limited. In our final post, I’ll highlight ideas I’ve seen on the ground that I believe do work for “all of the above”, and share where we see promise.