Denver built more than anyone else two years ago, and it's becoming (slightly) more affordable

Unfortunately, this is the exception. When affordable housing costs $600K per unit--for a worse product--but we can't build market housing for $200K per unit, we've got to change things

How Does Housing Become More Affordable?

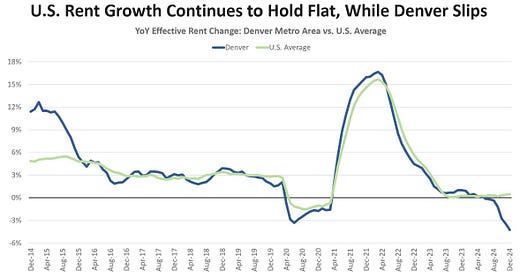

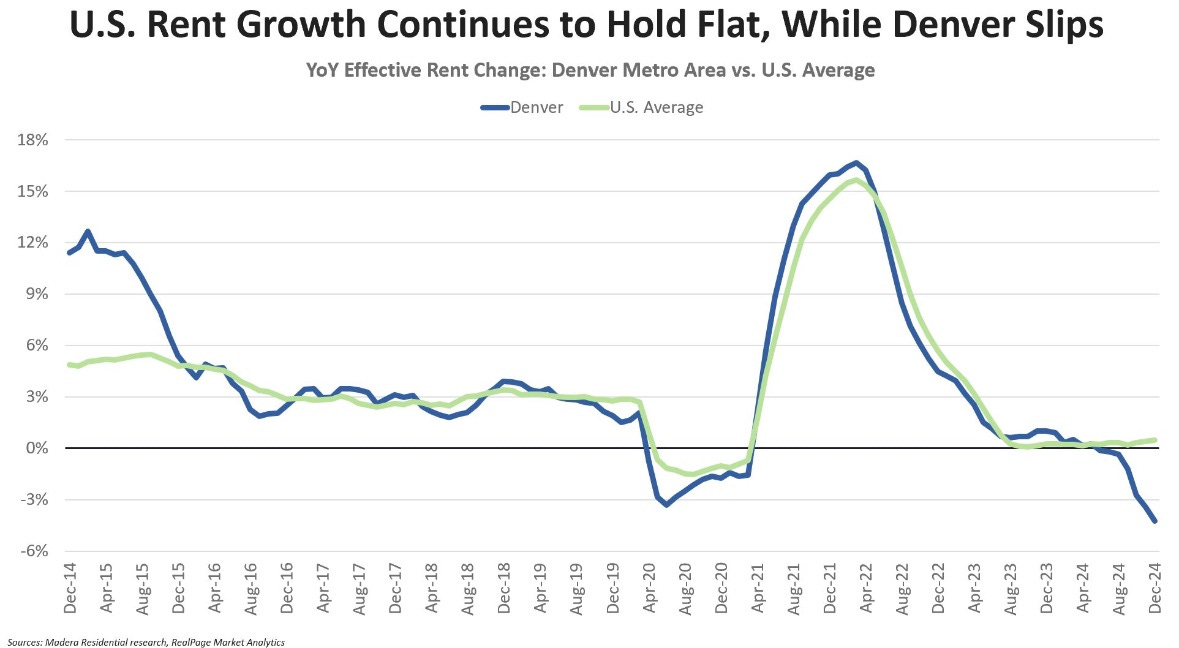

Breaking news: We are starting to see what rents look like at the end of 2024, and the results confirm what I’ve been arguing here—supply matters. There’s a pretty direct line between how many units were built in a city in 2022 and what 2024 rents look like. The numbers tell the story: cities that built more apartments two years ago are seeing more affordability today (no caveats or well-intentioned guardrails—see below, those can actually hurt!)

Take Denver, for example. In 2022, the city led the nation with 12,000 new units coming online. Now, in 2024, rents in Denver have actually declined by 3% from their 2022 levels. For apartment investors like me, that can be some tough news. But for a high-growth state like Colorado, where housing affordability has been a growing crisis, it’s undeniably good news. More housing means lower rent growth.

But here’s the problem: the two-year construction cycle that delivered relief in 2024 is about to reverse. Over the past couple of years, skyrocketing construction costs and high interest rates have crushed new supply. Developers across the country have hit the brakes, and the consequences will be felt in 2026 and beyond.

Source: Madera Residential Research; US Census

I saw this firsthand in Dallas, Texas, where we broke ground on a project in 2024. A city official told us in July that ours was only the third new project to start that year. In 2022, Dallas saw over 100 new projects break ground. That kind of supply drop-off guarantees that, barring a major demand shock, rents in Dallas and many other cities will start rising again in a couple of years. It’s not rocket science—it’s just supply and demand.

And yet, the dominant conversation around affordability continues to focus on taxpayer-subsidized low-income housing. While the goal of making sure lower-income families can find housing is important, the actual units that are getting built under these policies are often expensive, heavily subsidized, and ineffective at making a real dent in overall affordability.

A striking example comes from Austin, Texas, where a recent development proposal presented a choice. One plan would have delivered 600 market-rate units at a cost of $200,000 per unit, without requiring any government subsidy. Instead, the city council approved a 199-unit project, where each unit cost $615,000 to build—of which $200,000 was covered by federal subsidies. This is inefficiency.

I don’t blame the builders of these Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) units. They’re working within the constraints of what the city allows and what the federal tax code incentivizes. But the reality is that these kinds of projects do not move the needle on rent affordability. They help a small number of households while leaving everyone else to struggle with an overall housing shortage.

If we actually care about affordability, we need to focus on the policies that shape how many homes get built. Consider the cities where rents are rising the fastest—San Francisco, Los Angeles, Boston. What do they have in common? They make it incredibly difficult to build housing. Stringent zoning laws, endless permitting processes, and layers of bureaucratic red tape mean that by the time a project is approved, it’s often so expensive that only luxury units make financial sense. This isn’t a demand problem; it’s a supply stranglehold.

Contrast that with places like Houston, which famously has no zoning, and Phoenix, where permitting is relatively straightforward, and supply has been able to keep up with demand. Rents have been more stable there than in heavily constrained markets. Or look at Tokyo, one of the most affordable major cities in the developed world, despite high demand. Why? Because Japan’s national government has ensured that zoning laws allow for housing growth (very flexible zoning designations, and most areas are “by-right development”). When developers can build, they do—and rents stay in check.

With the national focus shifting toward government spending and getting the best value for taxpayer dollars, we need to apply that same scrutiny to housing. What actually works? The data shows that building more homes, period, is what drives affordability—not just subsidizing a few units at an astronomical cost.

Cities should be making it easier, not harder, to build. That means reducing parking minimums, allowing more apartments near transit and job centers, and reforming zoning laws that keep density artificially low. It means expediting permitting and making sure that well-designed, market-driven projects don’t get caught up in endless local battles. And it means recognizing that while affordability programs can play a role, they cannot and should not be the only solution.

If we continue to ignore supply, we will keep seeing these cycles: brief periods of relief when past construction delivers, followed by worsening affordability when new development slows. And what I really fear is a “doom loop”—low supply leads to high rents leads to high inflation leads to interest rate hikes leads to EVEN LESS supply.

Based on today’s construction slowdown, we are setting ourselves up for a painful few years ahead.

To borrow from an old Chinese proverb, the second best time to address housing supply is now (the best time was 20 year saog).